It looked like something that you’d only see in movies, but this is a real tragedy. TransAsia Airways’ Flight GE235, operated by an ATR72-600 (registration B-22816), took off from Taipei Songshan (TSA/RCSS) airport for a routine flight to Kinmen Shang Yi (KNH/RCBS) airport on 4 February 2015, where it lost power to all engines not long after take off, resulting in a fatal crash into the Keelung river just 5 kilometers departure.

The shocking footage

The final moments were captured by various dash cameras of Taipei residents as they drove along the Huangdong Boulevard viaduct next to the river.

The aircraft rested on the Keelung river inverted and initially media showed pictures of survivors seemingly unharmed escaping the aircraft. Initially no deaths were reported, but as the day progressed, the realities set in and the death toll mounted, up to 38 dead and 8 missing (as per 6 Feb at 1500UTC).

First sets of data from Flightradar24, my curiousity, and the flu

It wasn’t long before Flightradar24 released it’s ADS-B recordings of the accident.

It became immediately apparent that engine failure was likely, and news of the aircraft declaring an emergency citing “engine flameout” seems to confirm the suspicion. But, a twin-engined aircraft is designed to be able to survive an engine failure and land on the remaining engine, so obviously questions lingered in my mind for the rest of the day.

It became immediately apparent that engine failure was likely, and news of the aircraft declaring an emergency citing “engine flameout” seems to confirm the suspicion. But, a twin-engined aircraft is designed to be able to survive an engine failure and land on the remaining engine, so obviously questions lingered in my mind for the rest of the day.

Bed stricken with flu, there wasn’t much I could do for that day and the next, other than tweet pictures and my thoughts on the accident.

My initial analysis

I spent most of 5 February looking at the data from Flightradar24 and noticed the following:

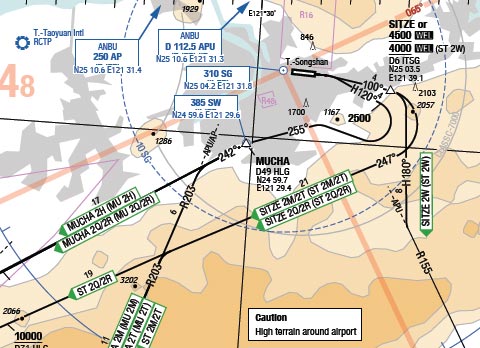

- The aircraft turned southwest as you would expect for propeller aircraft departing out of runway 10 at TSA (MUCHA2 SIDs)

- The crew may be concerned that they would not be able to climb above the mountains/hills (with terrain up to 2000ft) on the south east of the city or make the turn as per the departures, and decided to follow the valley to the east.

- Low ground speed throughout the event.

- Engine failure must have occured no earlier than 100 ft above ground level.

- Ground speed peaked very early on in the flight.

- Climb rate reduction was late, and the aircraft continuously lost height not long after that.

This is obviously, not your ordinary engine failure after take off. I initially toyed with the idea of shutting the wrong engine down, but I had nothing to go on to support the idea… until today.

The Preliminary Information

Today, the Taiwanese accident investigation body, the Aviation Safety Council conducted a preliminary information press conference regarding the accident, the most important being:

- The right-hand side engine had failed.

- For reasons yet to be determined, the flight crew shut down the left-hand side engine.

This, explained the questions I had. The flight data recorder plots also showed that the crew shut down the wrong engine. Now the question becomes…

Why did an experienced crew shut down the wrong engine?

To get the answer, I first collected the information gathered from the CVR and the textual outline of the FDR data together (ALL means both CVR and FDR):

- ALL 10:41:14.6 GE 235 flight recordings start

- CVR 10:51:12.7 Songshan tower issued takeoff clearance

- CVR 10:52:33.8 Songshan request GE 235 Contact Taipei Approach

- FDR 10:52:38.x Engine Warning (2)

- CVR 10:52:38.3 The main warning sound

- FDR 10:52:42.x Closed on the 1st engine throttle

- CVR 10:52:43.0 A crew mentioned engine recovery (One engine crew referred to recover)

- CVR 10:53:00.4 Both crew mentioned engine flameout procedure

- CVR 10:53:06.4 A crew mentioned engine recovery (One engine crew referred to recover)

- CVR 10:53:07.7 Members mentioned confirm engine #2 flameout

- ALL 10:53:09.9 Stall warning sounds (Until 10:53:10.8)

- ALL 10:53:12.6 Stall warning sounds (Until 10:53:18.8)

- CVR 10:53:19.6 A crew mentioned Engine #1 already feathered and the oil pressure was reducing

- ALL 10:53:21.4 Stall warning sounds (Until 10:53:23.3)

- FDR 10:53:24.x Off the 1st engine

- ALL 10:53:25.7 Stall warning sounds (Until 10:53:27.3)

- CVR 10:53:34.9 Contact Songshan tower crew call “mayday mayday engine flameout”

- ALL 10:53:55.9 Stall warning sounds (Until 10:53:59.7)

- ALL 10:54:06.1 Stall warning sounds (Until 10:54:10.1)

- CVR 10:54:09.2 Crew began to call engine restart (Members began to call again to drive)

- ALL 10:54:12.4 Stall warning sounds (Until 10:54:21.6)

- FDR 10:54:20.x Engine 1 Restart (Reboot the 1st engine)

- ALL 10:54:23.2 Stall warning sounds (Until 10:54:33.9)

- CVR 10:54:34.4 The main warning sound

- CVR 10:54:34.8 Unknown sound

- ALL 10:54:36.6 Recorder stops recording

- ASC explained that the warnings started about 37 seconds after takeoff (at an altitude of about 1,000 – 1,200 feet )

The above was translated from Mandarin into English with Google Translate and then edited for context (so excuse me if somethings don’t make sense on it).

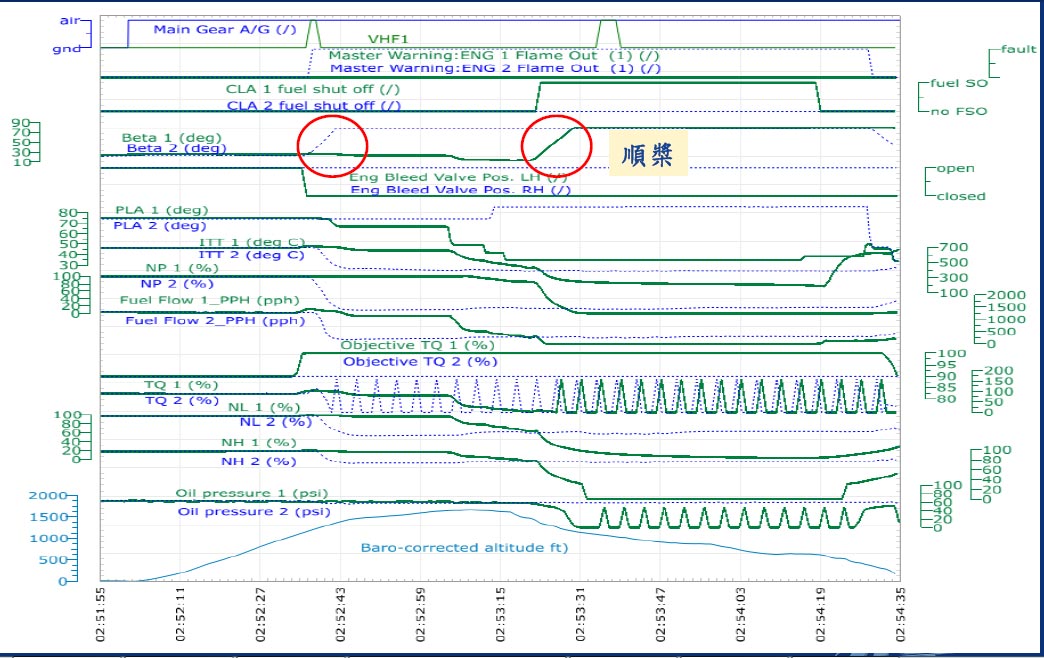

Then I looked at the FDR data:

What was found:

- Crew may not have conducted procedural callouts for engine failure.

- Autofeather of engine #2 was functioning.

- Power lever for engine #2 was not touched and Power Lever #1 was slightly pulled back upon engine #2 failure.

- 20 seconds after engine failure, Power Lever #2 was pushed forward. This would be consistent with a failure of engine #1.

- There was hesitation on pulling back Power Lever #1, taking more than 30 seconds for the lever to be pulled to idle in stages.

- In the middle of pulling back Power Lever #1, both crew identified that it was Engine #2 that had flamed out, but retarding Power Lever #1 continued.

- Condition Lever #1 was placed at Fuel Shut Off a few seconds after Power Lever #1 was placed at idle. This shuts down Engine #1.

- It was not until some 30 seconds later did anyone call for an engine restart, and almost 1 minute after the fuel to Engine #1 was shut off, did the Condition Lever #1 was taken out of fuel shut off (probably at “Feather” given the Beta 1 readout at the end of the flight), this together with the Power Lever #1 a idle commenced the auto-restart process for engine #1.

- As Engine #1 was relit, Power Lever #2 was placed at idle, and auto-restart process for Engine #2 was started.

- Condition Lever #2 was not placed at Feather (engine unfeathered when restarting, per Beta 2 readout), this is not a wrong move.

No Callouts leading to confusion and a tragic outcome

I discussed the above with a current ATR72-600 pilot, and unfortunately our conclusions were brutally simple. If the CVR information released is complete, then failure to make the required callout for engine failure and a timely identification of the failed engines, causing confusion resulting in the wrong action by the crew. The crew did not effectively identify which engines to shut down resulting in shutting down the wrong engine, where putting the flight into an unsafe situation.

The pilot flying would have been focusing on flying the aircraft, and would have been mystified by the lack of power, but realized quickly that he would not have been able to continue the Standard Instrument Departure which would have risked flight into terrain.

By moving the Power Lever #1 to idle, and then put Condition Lever #1 to fuel shut off, the crew had feathered and shut down a functioning engine and the confusion led to the delay in correcting the errors, when finally the Condition Lever #1 was moved out of fuel shut off, enabling the auto-start. This undoubtedly delayed putting the Power Lever #2 to idle to enable re-start for that engine as well.

The pilot flying would have had to focus to keep the aircraft flying for as long as possible, and in this case, avoid dense built-up areas, and he had to rely on the pilot monitoring to do the troubleshooting and corrective actions to the erroneous engine shutdowns.

At the very end, the crew did restart Engine #1, and was restarting Engine #2, but it was too late.

What they could have done despite the error?

Wishful thinking, but had the crew placed both Power Levers at idle, Engine #2 could have restarted despite erroneously shutting down Engine #1. Had they have made the necessary callout, disaster would have likely been averted.

Closing Remarks

This article isn’t to judge the flight crew, as obviously it is based on very few data and the assumption that the crew did not make the engine failure callout and identification in a timely manner. As dead pilots cannot defend themselves, the question arising from this article should not be whether or not the accident was caused by pilot error, but we should question why the crew made the errors, so that we can understand the factors that led to the error, and prevent a future repeat.

We can expect the Taiwanese Aviation Safety Council to look into these questions in much greater depth, and come out with credible explanations as to what caused the errors and what factors were at play to produce the error.